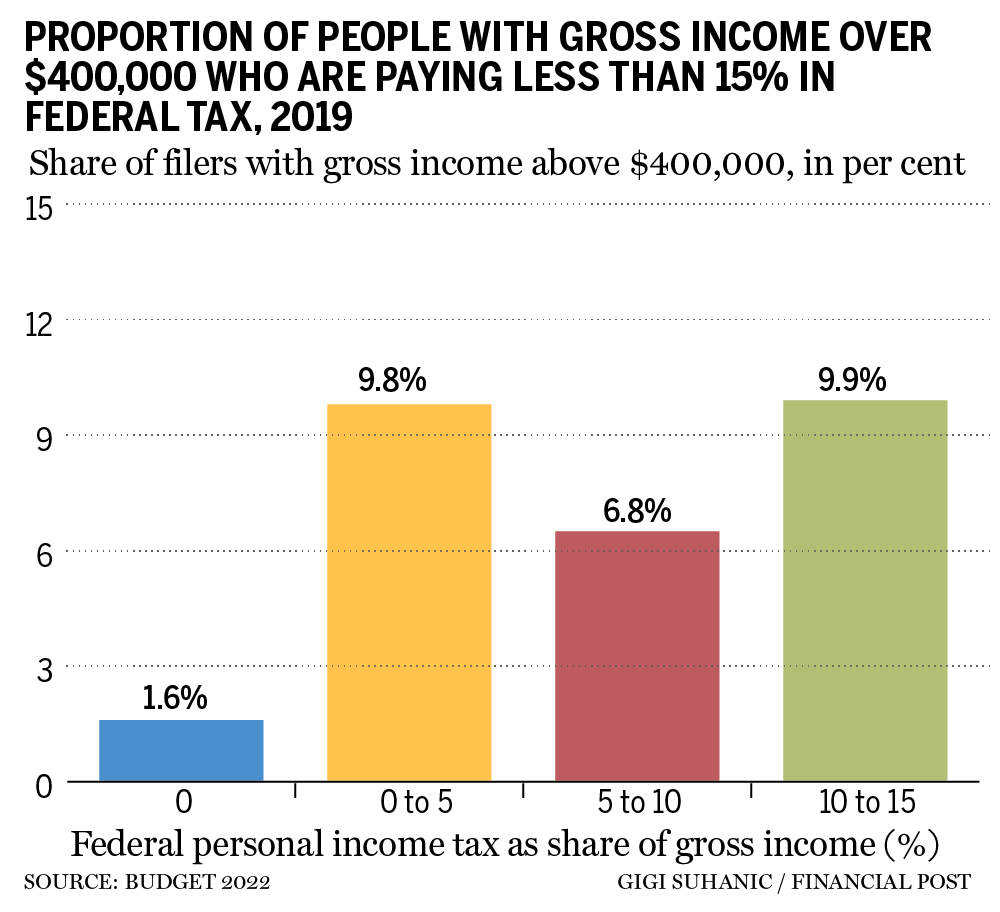

One of the more curious items in last week’s nearly 300-page federal budget was an ominous statement that “some high-income Canadians still pay relatively little in personal income tax as a share of their income.”

The budget document provided some stats, using 2019 tax data, that showed 28 per cent of filers with gross income of more than $400,000 (which was the top 0.5 per cent of all income earners), or about 41,400 individuals, paid an average federal tax rate of 15 per cent or less by using a variety of tax deductions and tax credits. More granularly, the data show that nearly 18 per cent of those top income earners (about 27,000 Canadians) paid less than 10 per cent in federal tax. And apparently 1.6 per cent (2,400 filers) paid zero federal tax.

The data was published as a way of introducing the government’s review of the alternative minimum tax (AMT), the results of which will come out in the fall economic update. But are these numbers actually a concern? Is there anything nefarious about such a low effective rate? Or are taxpayers simply following the law in accordance with the well-accepted Duke of Westminster principle that states “taxpayers are entitled to arrange their affairs to minimize the amount of tax payable.” Based on a 1936 tax case in the United Kingdom, this principle was confirmed most recently by Canada’s Supreme Court in a November 2021 decision.

It’s a question worth exploring. To begin, keep in mind the budget stats only looked at the federal tax rate and not the combined federal/provincial rate. Currently, there are five federal income tax brackets for 2022: zero to $50,197 of income (15 per cent); more than $50,197 to $100,392 (20.5 per cent); above $100,392 to $155,625 (26 per cent); over $155,625 to $221,708 (29 per cent); and anything above $221,708 is taxed at 33 per cent.

Due to the graduated, progressive rates on the first $221,708, the federal tax for 2022 on $400,000 of ordinary income would be about $109,000 for an average federal tax rate of about 27 per cent, before considering tax-preferred income and various other deductions and credits.

Capital gains are only 50-per-cent taxable, meaning that an individual who realizes a one-time gain on the sale of their cottage of, say, $400,000, would have gross income of $400,000, but taxable income of $200,000, because only half the gain is taxable. Absent any other income, the federal tax bill would be about $43,000 and the average federal tax rate would be 10.8 per cent on capital gains. But is the cottage seller, who had one year of very elevated income, truly a “high-income” earner on which the government needs to charge an AMT?

A quick look at the 2019 Canada Revenue Agency income statistics for the 2017 tax year (the most recent publicly available data) shows that 51 per cent of the returns by the highest income earners (defined for these statistics as those making more than $250,000), about 312,000 Canadians, reported a taxable capital gain, with the average being just over $125,000, which would likely indicate the average capital gain was about $250,000.

Next, let’s consider an investor who earns $400,000 in Canadian-eligible dividends. Because of the dividend tax credit, equal to 20.73 per cent of the actual dividends received, the federal tax on $400,000 of eligible dividends would only be $76,000 for an average federal tax rate of 18.9 per cent, which can also lower the average tax rate from the expected rate. Two-thirds of the highest income earners in 2017 reported some Canadian dividends, with the average amount being more than $100,000.

Of course, tax deductions can also reduce your average tax rate. The top three deductions (by total dollar value) claimed in 2017 by the highest income earners, were the registered retirement savings plan (RRSP) deduction, lifetime capital gains exemption (LCGE) and the employee stock-option deduction.

Canada Revenue Agency data for 2017 shows 60 per cent of top income earners claimed an RRSP deduction (average claim of $38,730, meaning some taxpayers were clearly catching up on unused RRSP contribution room). And while the stock-option deduction for employees was taken by only four per cent of the highest income earners, the average deduction was almost $152,000. (This will likely start to go down in future years since the rules limiting the benefits of the stock-option deduction were changed as of July 1, 2021).

In 2022, the LCGE eliminates taxes on $913,630 of capital gains from the sale of qualifying small-business shares, and $1 million of capital gains on the sale of qualified farming or fishing property. The CRA data show that nearly 18,000 of the highest income taxpayers in 2017 claimed LCGE deductions valued at $4.6 billion, with the average claim coming to about $260,000, which is the equivalent of $520,000 of tax-free capital gains. This will likely explain the zero tax rate for some taxpayers in the 2022 budget document.

Finally, on the credit side, are charitable donations. A high-income earner who makes a large donation of, say, $100,000 to charity, would be entitled to a federal donation tax credit of 33 per cent. The tax payable on $400,000 after considering the donation tax credit for a $100,000 donation would be about $75,000 for an average federal tax rate of 18.9 per cent. The CRA data show that 64 per cent of the highest income earners in 2017 reported a charitable gift, with the average gift being $17,389. Charitable gifts, depending on the quantum, can significantly reduce your average tax rate.

We already have a federal AMT at a 15-per-cent rate. If the government wishes to preserve the full benefits of charitable giving, keep integration intact by allowing the dividend tax credit designed to minimize the double taxation of corporate income, and maintain the lower capital gains inclusion rate or the LCGE on the one-time sale of a cottage, business or farming or fishing property, there’s little tax revenue left to reap in an updated AMT, particularly given the changes already introduced last year on employee stock options.